The Rosetta stone was found in Rosetta outside of Alexandria year 1799. The stone was inscripted with the same text in three different languages; at the top: hieroglyphs, followed by ancient Egyptian, and at the bottom classical greek. The Rosetta Stone had a crucial part in solving the mystery of the hieroglyphs. Before it was found, the hieroglyphs where merely images lacking of their original meaning.

The more an object is being used – or a phenomenon for that matter – the more that thing is charged with meaning. Including everyday objects such as a calculator, your toothbrush, or the streets we walk upon. The more frequently something is utilised, the faster it gets charged with meaning. Even if it in that specific time and place may be regarded as something with low, or none, economic or cultural value; it could still be of historic significance.

In that light, you could definitely see the discovery of the Rosetta stone as something almost magical. In a blink of an eye it turned something that up until then viewed as insignificant into something complex; and managed to breathe life into something that was dead. The very moment in year 1822, when Jean-Francois Champollion managed to decipher the hieroglyphs, a big change happened. They went from being images to symbols.

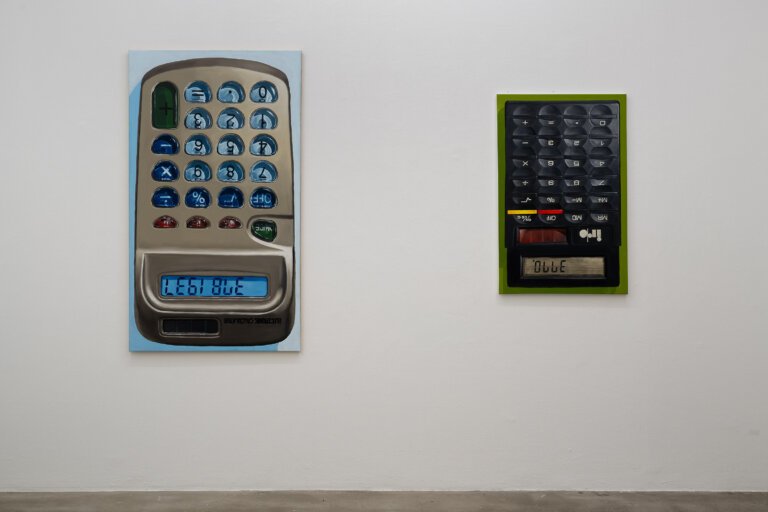

I remember when Joel, who sat behind me at math lessons in 7th grade, showed me his calculator where he had written 0.7704. When I looked at him, puzzled, he elegantly flipped the calculator around and the word hello appeared. Joel introduced me to something that has been handed down through generations of bored students; a secret language that made it possible to decipher calculators, and turn numbers in to letters. For years to come I tried to come up with new words that was possible to write with the limited letters that you can produce on the display of a calculator.

In my artistic practice I draw inspiration from the everyday object, the folksy nostalgic, and the kitsch of popular culture. I’m interested in what usually isn’t considered to have cultural or economic value. Things that we surround ourself with, and that in some sense create a contemporary mythology.

Thomas Hansson Stockholm, november 2024

Thomas Hansson was born 1984 in Svedala, lives and works in Stockholm and got a Master degree in Fine arts from the Art academy in Umeå 2016. Previously, his work is shown in Sweden, Denmark, Czech Republic and Germany.

’Mathematics and other forgotten languages ́ is Thomas Hanssons first exhibion in Gothenburg.